LA MEZCLA NEIGHBORHOOD REACTIVATION

design research | concept | rapid prototyping | service design

Team

Manali Mohanty, Jennifer Cob, Wolfe Erikson

San José is the capital of Costa Rica, a bustling city with a 2 million strong metropolitan population. The city presents unique challenges in mobility, influenced by infrastructure, weather, safety and accessibility. In the wake of Covid-19, the mobility needs among Tiques (gender inclusive term for Costa Ricans) are changing. As a team, we began our explorations in questioning how and why the city of San José moves.

The Brief

Design mobility services and interfaces in San José, Costa Rica for a more regenerative world.

Research Methods

Guided walk with economist and city planning expert Federico Cartín

Nighttime observational walks

Timed observations (migration patterns) of various public gathering spaces.

Interviews of local residents

Interviews of local business owners

Expert interviews

Population Emphasis

GenZ and Younger Millennials (22 to 31 years old)

Observational Studies

Federico Cartín led us through the urban environment of San José. He showed us some of the challenges of the city including limited and slippery bike lanes, a train that was prone to accidents, and narrow roadways that often disregarded pedestrians. On our walk we learned that the main thoroughfare ran east to west through the city and was dotted with several urban green spaces.

Map of downtown San Jose showing the green spaces along the main thoroughfares

Each urban green environment had its own vibe, some of which vibrated with chatter of people meeting with friends and family, while some remained empty.

Touring San José with Federico Cartin

Observing usage of green public spaces

Sketch studies during ‘rush hour’ at the park

Documenting flow of pedestrian traffic

Conversations with Local Residents

Our goal as a studio was to understand the motivations and barriers to moving about the city as the Global Pandemic was deep into its second year. We framed our first round of interviews around these questions:

What is the motivation of mobility?

Why are people moving throughout San José?

What do they need to be able to move with more ease?

Interview Highlights

“ I would love more places where people can hang out without any concerns or risks [crime & covid exposure].” — Alita (22)

“I really enjoy walking from one park to another in San Jose, and going for an ice cream and just hanging out.” — Margarita (31)

“We had to find other ways to hang out [because of Covid], [we] usually go to friend’s houses” — Tony (28)

Interview footage of Margarita explaining that beauty may be an impediment to where someone might choose to gather in San Jose

Interview Footage with Tony explaining how the changing migration patterns of Covid may have made some places unsafe in San Jose

Insights

Although we set out to address mobility issues in San José, we were beginning to realize that mobility is the precursor to gathering, and there was a significant gathering issue. People needed more safe spaces to gather with loved ones. Some distinct curiosities formed from these conversations and learnings. Why were some parts of San José more “beautiful” than others? What parts of the city did people feel safe in?

We asked participants to map where in the city they like to go, versus where in San José they might avoid. Below is the visualization of that data. As you can see, there are clear “safe” hubs that are heavily trafficked by pedestrians running east to west in the city. Every person we spoke with named Barrio Escalante as a place where they regularly go, and every person named Museo de Los Ninos (The Children’s Museum) as somewhere with high risk of crime.

Data Visualization

Data visualization of where San Jose residents gather, and where they avoid due to reputations of crime.

Combined data visualization for where San Jose residents gather, and areas they avoid. The larger the circle, the more times it was brought up by interviewees.

Key Insights

Insight #1: Stories

Someone’s perception of the safety of a neighborhood is based on stories and insights from people they trust within their community

Insight #2: Community

People’s craving for connection is a deep motivator in their decision to seek safe spaces to congregate in the city. This in turn draws others, thus creating new mobility patterns in the city.

Evening Observational Studies

To get a sense of residents’ gathering patterns after work hours, we spent some evenings exploring the streets of San Jose. Comparing two major public parks in the Barrio Escalanté neighborhood - Parqué National and Parqué Francia. The disparity between the two was jarring:

Parque National, despite its proximity to San José’s hottest party spot, La Cali, was nearly empty. The much smaller Parqué Francia on the other hand was buzzing.

We asked some of our research participants why they might want to hang out in Parque Francia as opposed to Parque Nacional.

“To be honest, this park [Parque Nacional] has been like a male prostitution park for a long time. I think that in the last 10 years, even in the last year, things have changed so much. For example, Parque Francia is like free love…and maybe even gays chose [Parque Nacional] because it was kind of like, in an area that was shady.” — Mariana (Owner of Local Pizza Restaurant)

“I don’t know why we don’t use Parque Nacional. We go get drinks in La Cali and food all around, but we never stop to chill in that park.” — José (local San Jose resident)

We continued to hear stories of Parque Nacional’s sketchy past, and became curious if they reflected the environment as it exists today. We met with some local police officers and asked them about the crime rates in the Parque Nacional area. They said “Nothing really happens here”. In fact, they said Parque Nacional was incredibly safe and that the risk of crime was a misconception. It seemed as though the reputation of crime in the area was the preventative barrier in why people might view Parque Nacional as an option for gathering.

Hypotheses for lack of gathering in Parque Nacional

Stories sometimes hold more weight than current evidence. Even though Parque Nacional has been much safer in recent years, the public perception of the place remained.

Parque Nacional’s infrastructure didn’t encourage face to face gathering. Bench seating catered to side by side interfacing. It was also poorly lit and felt dark after sundown, especially near the more heavily obstructed parts of the park due to the density of trees.

Proximity of the train station created a “pass through” environment. We noticed a lot of movement through Parque Nacional, but not many stayed to linger or gather. We theorized that this was due in part to the location of the train station. People getting on the train to leave work, or getting off to come into the city.

Hypotheses for why people gather in Parque Francia

Access to necessities, nearby restaurants, markets, and bathrooms

Knowledge that people will be there upon their arrival

Well lit and open space making it easy to find people

By this point, we felt confident in the problem that needed to be solved.

Problem Framing

Shaping the Solution

We began ideating on what different strategies of neighborhood rehabilitation might feel like for the Costa Rican context. Through our interviews we learned that local Tiques’ key motivations for gathering were safety, beauty, and knowledge of where people were going to be. With this in mind we spoke with Yuliya Bruk, Creative Director and Founder of Future–·Arts. Yuliya utilizes urban placemaking to build bridges between artists, corporations and neighborhoods.

This idea of sense-making–being able to replace memories, or at least form new ones, was rather interesting to the studio. We began to break down the elements of the gathering. One information resource that was quite helpful was “The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces” by Whilliam H. White. Here are some important elements we considered from this research as we went into ideation:

“What attract people most, it would appear, is other people”

On Benches: “They are not good for sitting. There are too few of them; they are too small; they are often isolated from other benches or whatever action there is on the plaza.”

On Chairs: “If you know you can move if you want to, you feel more comfortable staying put”

We dove into ideation with this question in mind: “how might we leverage urban placemaking in order to generate new associations to Parque Nacional”. The potential interventions varied from collaborative and interactive art installations to throwing a neighborhood block party. We placed the potential design paths onto an effort/impact graph which helped us to choose a viable option within the time and resource constraints we needed to consider.

Impact versus effort graph that the team used to determine what intervention to move forward with.

La Mezcla

The intervention we moved forward with was La Mezcla (The Mix).

It is a regenerative approach that finds solutions for both residents who need more safe places to congregate, and local restaurants that are struggling due to the global pandemic. Centering these two populations, we created an infrastructure that could bring them together.

Costa Rica has recently passed the ‘Open Air Commerce Law’ in January, 2022 — which allows for municipalities in Costa Rica to give temporary permits to restaurants, bars and cafes to extend their reach to public spaces. La Mezcla offers restaurants support in applying for these permits, as well as a simple infrastructure that leverages the built environment and offers a safe and comfortable space to gather within Parque Nacional. When arriving at La Mezcla, a host would greet you and show you the QR code that populates the La Mezcla app, which shows the many menu options of neighboring restaurants. Simply order whatever food or beverage item you would like from the app, and wait for the La Mezcla staff to deliver the order directly to you in the park.

1. Make a plan to get together with a friend

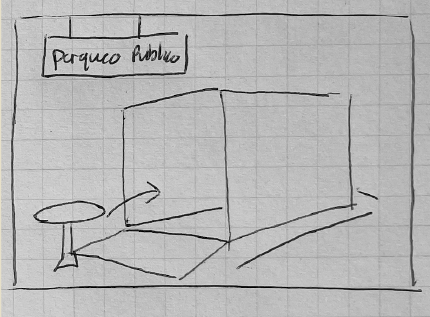

5. The host brings the guests to their table

9. Guests order food from neighboring restaurants and pay

13. Tables are cleaned after each guest by La Mezcla staff

2. Decide on the location where you want to meet

6. Guests find QR code on the La Mezcla table

10. Restaurant receives the order and the chef prepares the food

14. Tables and chairs are put into storage after service

3. Wayfind to La Mezcla tables using maps posted on location

7. Guests scan the QR code on their table

11. Food is picked up by La Mezcla staff

4. La Mezcla host greets the guest and introduces the experience

8. The QR code pulls up the La Mezcla App

12. Food is delivered to the guests’ table by La Mezcla staff

Prototype Testing

We built a simple low-fidelity digital experience to be able to test with. We were seeking confidence in our design decisions in various points of the experience, namely the wayfinding from the host, locating and scanning QR code to bring up the La Mezcla website, and what the delivery experience felt like.

During the testing session we were surprised to see how many people passing through Parque Nacional stopped to investigate La Mezcla. Several took the opportunity to scan the QR code to bring up the La Mezcla app. It seemed as though the people of San Jose were ready to gather, they just needed an offering that solved some seating infrastructure and reputational issues.

From the testing we learned that there may be some confusion from the patrons in whether or not their food needed to be collected, or was to be delivered to them. An observation to be refined with further testing.

The La Mezcla service blueprint mapped the complex ecosystem it will exist in, from city government to restaurant coalitions and financial services.

Service Blueprint

Necessary for La Mezcla to operate:

Digital:

Create & maintain app

Set up payment system

Operations:

Identify location (opportunity to expand beyond Parque Nacional)

Give guidance on applying for municipality permits to restaurants

Plan and allocate space for customers

Sign up neighborhood restaurants

Execute contracts with legal team

Get permit for storage solution

Logistics

Hire and train installation, break down, and cleanup crew (periodic)

Hire and train host and delivery staff (periodic)

Implement storage solutions (tables, chairs, etc)

Prepare location with signage, furniture, lighting (daily)

Breakdown, cleanup, and storage (daily)

Ecosystem map for La Mezcla

Impact & Future Ripple Effects

La Mezcla’s impact will be three pronged — environmental, social and economic. A percentage of profits will be donated to local greening programs and leftovers will be repurposed. Connecting communities to local enterprises will result in rehabilitation of neglected neighborhoods. New culinary corridors between La Mezcla locations will encourage walking thereby positively impacting general health and wellbeing of local San Jose residents. And lastly, increased business and tax revenue promises to be regenerative to the entire downtown ecosystem.

Neighborhood restaurants will thrive and grow from the increased revenue generated, as will municipalities. In turn increasing funding in public spaces and attracting new and diverse businesses to these areas. Over time the three fold ripple effect of La Mezcla promises to be a sustainable regenerative solution for this vibrant capital city.

La Mezcla’s operation is highly scalable and has the opportunity to extend beyond the reach of Parque Nacional into neighboring green spaces like Parque Morazon and Parque España.

Future Considerations

How might we honor the history of places we inhabit (recognizing the importance of Parqué Nacional to the queer community)?

Are there opportunities to serve food vendors not currently in a storefront setting (food cart vendors etc)?